I carried out the following interview with Ian McKellen about his landmark performance as Richard III backstage at the Theatre Royal, Nottingham, in 1991, while still a student. I remember being so nervous that I had to have a whisky beforehand in the theatre bar.

My appointment was for 6.30pm, with McKellen due on stage that night at 7.00pm playing the Earl of Kent opposite Brian Cox's King Lear. His first words to me upon opening his dressing room door were an apology for "stinking the place out with camembert". He couldn't have been nicer, and later approved my copy with a very kind postcard sent from the Teatro Milano. The interview was published in the journal of the Richard III Society.

Hand in hand to Hell: Ian McKellen as Richard III

As the climax approaches of the Royal National Theatre's production of Richard III, lan McKellen is hoisted aloft on a hydraulic lift to address his black uniformed army, the auditorium resounding with the Nuremberg-style chants of "Hand in hand to Hell". This is Shakespeare with its politics to the fore; drama with a distinct and highly disturbing contemporary edge.

Ian McKellen, at fifty-one years of age, is perhaps the finest classical actor of his generation. The knighthood he received in the New Year's Honours List can only be described as fitting recognition for one of British theatre's most remarkable talents, responsible for a series of electrifying performances in roles such as Richard II, Macbeth and Coriolanus. Sir Peter Hall reputedly said of him that he could be downstage in the dark with his back to the audience and still be the centre of attention. Surely there can be no better definition of a star.

Now McKellen is back at the National, producing the most ambitious tour in its history which takes in venues as diverse as Cairo and Prague, as well as playing the Earl of Kent in King Lear and the title role in Richard III. He recently took time out of his busy schedule to talk to me about his mould-breaking performance as Shakespeare's demon king.

"I think it was about a year ago, or maybe even a little bit longer than that. Richard Eyre asked me to go back to work at the National Theatre, and I said that I would like to do that, particularly if there were a possibility of doing a touring production." McKellen speaks in measured tones, his rich smooth voice betraying just a hint of his native Lancashire accent. Reclining in a dressing room chair and taking occasional drags on a cigarette, he thinks deeply before answering each question. "I imagined something along the lines of the small scale tour I did for the RSC ten or twelve years ago where we went to a lot of places that didn't have theatres, and a few that did, setting up the productions wherever we could, in village halls and so on. But he had it in mind that we should do a touring production, in large theatres as it's turned out to be, and that that should be fitted in with an international tour, which was something the National was always getting requests to do."

Set in the 1930s, Richard Eyre's production of Richard III succeeds in totally altering one's perceptions of the play. Instead of a grotesque, blood-spattered comedy, he provides a riveting study of the overthrow of a lawful government by the fascist elements lurking within it. McKellen admits to it being "a rather happy style of presentation" in the aftermath of the great Eastern dictatorships, but says that the European tour did not directly influence the approach. "It came about through the association of Bob Crowley, the designer, and Richard and myself, and I think we can all take credit or blame for the overall concept, which, strong as it is, didn't seem to us when it began to emerge from our conversations to be anything other than a response of three people to the words that they were reading, namely Shakespeare's words. We were talking about the play in general, and about scenes in particular and the characters, and we found we were discussing them in terms of modern politics. It was that aspect of the play which seemed to illuminate everything in it."

One of the most positive results of the modern setting is the way how characters are divided into types easily recognisable to a twentieth century audience: there is Hastings, the muddled appeaser who bears an uncanny resemblance to Neville Chamberlain; Catesby, the ambitious and unscrupulous private secretary; and Buckingham, an amoral schemer of Bismarckian proportions. "It's helpful if people can understand who is royal and who is not, who is a politician, who is a civilian, who is a soldier and what rank of soldier, and so on... These things are very clearly laid out, it seemed to us, in the text, but it can't always be clearly understood if everyone's wearing medieval costume that now looks like fancy dress to us."

The effect of this is aesthetically startling. Urbane characters in evening suits and white ties, or the khaki of the British officer class, stalk a shadowy world lit by metal-shaded interrogation lamps. Nothing is conjured up so much as the dreamscapes of Franz Kafka, especially during a macabre, candle-lit dinner party at which Richard first confronts his enemies, the Woodvilles.

"The danger is, of course, when you make it modern that you exclude areas of the text which are not modern, like the cursing and that rhetorical side of particularly the women's mourning, and so on. But that I think would always be problematic and not explained, or any easier for an audience to take if everyone were dressed in medieval clothes."

McKellen's Richard, itself, is a revelation. Gone is the twisted cacodemon, and in its place is a very real human being, who is all the more frightening because of it. "In this play, as opposed to seeing him as a character in the Henry VIs as well, the deformity is much less of an issue, and, although he brings it up himself in ironic terms, it didn't seem to me appropriate to try and be the bottled spider, or a bunch-backed toad. Those are insults, they're not descriptions."

As sounds of battle fade and the curtain rises on a smoky stage, McKellen, dressed in a khaki greatcoat and peaked officer's cap, walks stiffly towards the audience. Speaking with clipped, Sandhurst vowels, he launches into the famous opening soliloquy: "Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer by this sun of York…"

"Like Iago, like Macbeth and like Coriolanus, what's being investigated in part is a professional soldier, who is out of work. All the trouble in Cyprus with Othello and so on, happens when these soldiers are not working. They're fine until suddenly they've got time on their hands. Coriolanus's problems all come from him trying to adjust to civilian life, and Richard III is the same. So there's something that he shares with those other great soldiers, and Richard is undoubtedly a great soldier; it doesn't fit him to be a great politician, or a great man of civilian life. For the rest, it's clear that his deformity is of great concern to him, and in our version he hides it and copes with it. Obviously, psychologically, the fact that he's never been loved, particularly by his mother, is of great worry to him; he doesn't seem to have any close friends; he doesn't seem to have had any success with women... All his life has been, therefore, a revenge on the world because of the way it's treated him."

Given McKellen's reputation for seizing upon contemporary equivalents of the characters he plays, I asked if the extensive research involved in his portrayal of Hitler for Granada Television's Countdown to War had contributed to his view of Richard.

"The details of his political involvement did have some connections with Hitler, but not psychologically. I mean, he made sure that he was elected King in a way that Hitler was elected as Chancellor; there wasn't a coup d'etat; there wasn't an armed revolt. He did it all apparently legally, but in fact killed people on the way and told lies, and so did Hitler. But as a man, Richard just seemed to spring so clearly off the page that I didn't do the normal thing of wondering who he would be were he living today. There are so many examples of tyrants in our century that I didn't need that sort of preparation."

This is a Richard seen through eyes unclouded with sentimentality and the character that emerges, in stark contrast to Derek Jacobi's comic tour-de-force at the Phoenix in 1989, is never less than chilling. But does this inhibit his extraordinary rapport with the audience which is such a corner-stone of the play?

"Richard's relationship with the audience may be something that I'm growing into and initially didn't quite have, and if I were playing him as the jolly villain, as a sort of Punch in a Punch and Judy show, then that relationship would be easy enough. But I think if the audience starts laughing with Richard, then you're robbing the play of much of its intention. There is nothing funny about what Richard does. There may be something amusing and entertaining about the way in which he presents it, but by the end Richard has to have that amazing revelation to the audience in his last soliloquy where he's analysing the nature of his own behaviour. And, I don't know, it's a great problem with the part and I don't think I've quite resolved it yet."

The final soliloquy, in which Richard is tortured with guilt for his deeds, is preceded by a spectacularly staged nightmare. The ghosts of his victims appear to torment him, and Buckingham delivers the coup de grace by pressing a crown shaped from barbed wire on to the usurper's forehead. Throughout all this, a magically rejuvenated Queen Margaret circles the action, laughing maniacally as her prophesies of doom are fulfilled.

"In the text they're referred to as ghosts, those visions, but it's quite clear that he's having a nightmare and that Richmond is having a dream and somehow they're both in each other's dreams. And I said, if we could stage it like a dream, then we were going to be a lot closer to what was required than normal. I think we could have gone further. We could have had Richard looking at himself, maybe... But when I'm playing it, I just see it all as an extraordinary pageant of life flashing quickly before him and it's all an emotional preparation for the speech that follows."

The Battle of Bosworth is thrillingly presented in medieval armour, and Richard is butchered in the midst of his opponents, rather than in single combat with Richmond. Sliding across the stage towards his sword like a wounded scorpion, he dies uttering a pitiful repeat of the cry "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!"

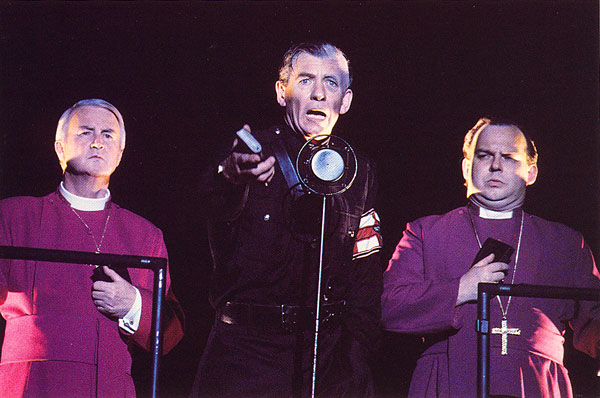

One emerges from the auditorium, still reeling from the sheer theatricality of the experience. It is a production full of haunting moments, but perhaps none more so than Richard, a bible in his hand and a priest on either side, standing on the battlements as he prepares to accept the crown from the credulous citizens of London below. His face gleams in the cold rays of searchlights and his amplified words echo through the darkness. "We put the bible in earlier in the play as if that were something he might have in his knapsack. I don't think you can suddenly have that scene with him parading himself as a holy man of prayer if it's not been prefigured elsewhere. Otherwise it just becomes a charade and everybody is a fool to believe it. It's much more potent, I think, if Richard is so convincing as a righteous man that we would be fooled by him. Normally that scene's played for laughs. I think, if it does that, then the horror of the situation is removed…"